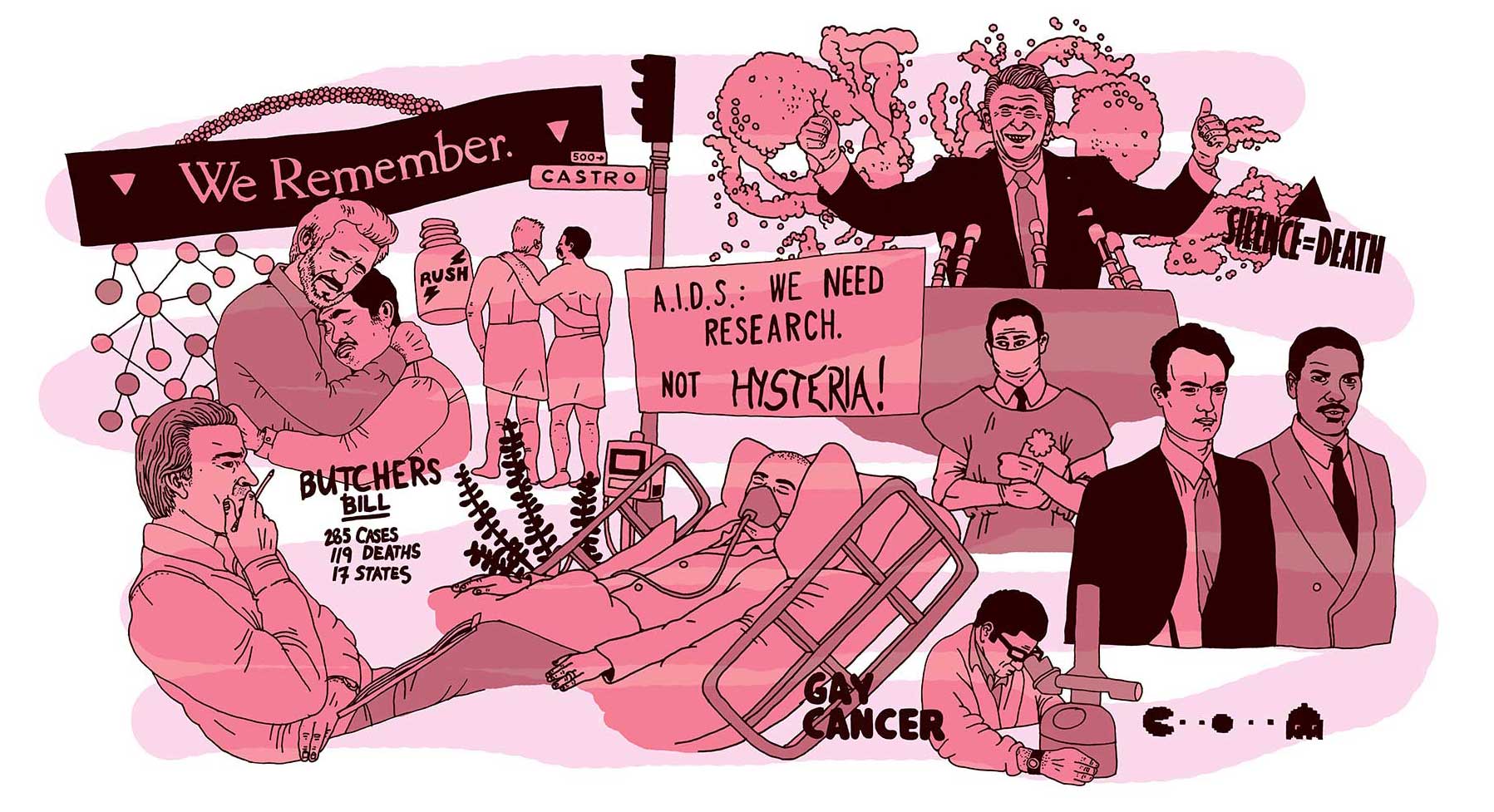

Since 1981 and the first cases of what was later to be called HIV and AIDS, moving images and film – like always, mostly American – have played a big part in how society has come to understand and be informed about the epidemic. According to many surveys over the years, more so than from sources like friends, doctors, school or newspapers. And, like the majority of films in film history, the stories have mostly been made by men, about men. In the 1980s, typical media representations of AIDS in the US were also under the influence of the political clout of the religious right and their conservative ideas about sex and LGBT issues. The early story of AIDS was all about "family values", homophobia, stereotyping and fear of the other.

Even though it was clear very early on that women, children and heterosexual men were being infected too, the patients in the news stories in the 1980s were almost exclusively gay men. Visual representations were produced and copied, copied and produced, quickly formed conventions. And so, the public agenda was set and the face of AIDS was shaped. The idea of the epidemic as a “gay cancer” not only caused victim blaming, it also gave way to ignorance and misconceptions about who needed to protect themselves and who didn't. The effect was disastrous. The "general public" and president Ronald Reagan got the idea that they didn't really have to care. The disease was something that happened somewhere else, to other people who had themselves to blame.

American journalist Ann Giudici Fettner (author of the 1984 book The Truth About AIDS: Evolution of an Epidemic) and author/AIDS activist Simon Watney, both speakers at the international AIDS conference in Stockholm in 1986, talk about the responsibility and the important role of mass media

Up to the early 1980s, homosexuality in the movies had mostly consisted of mere suggestions, cartoonish stereotypes in comedies or, in dramas, a problem that not seldom ended in loneliness, alcoholism or suicide or a combination of the three. Now there were suddenly more gay men in mainstream media – but almost all in connection to AIDS. Gay men came to be so closely associated with the epidemic that they by many were seen as inherently dangerous. Perhaps as a reaction to that fear, a new masculine ideal was formed in mainstream movies. The pumped up and suntanned bodies of stars like Sylvester Stallone and Arnold Schwarzenegger were everywhere, and the contemporary action films were all about the return to old school values. They were far from the city decadence, dark clubs, promiscuity and David Bowie's blood drinking vampire in director Tony Scott's AIDS tinted The Hunger from 1983.

In 1985, when 50% of respondents in an LA Times poll favoured quarantining people with AIDS, something changed public opinion. In July, the iconic square-jawed Rock Hudson became the first major American celebrity to publicly acknowledge having AIDS. If he could have it, anybody could have it. The number of articles on AIDS shot through the roof, a movement in Hollywood formed to battle it. Even though grassroot activists, doctors and researchers had been trying to draw attention to the AIDS crisis since the beginning of the epidemic, it took a famous face to change the public view.

Another famous face, Elizabeth Taylor, became the first globally recognized HIV and AIDS activist. A feature film about Taylor focusing on her activism is reportedly on its way, and the documentary The Battle of (amfAR) tells the story of how two early AIDS organizations – co-founded by Taylor and medical researcher Mathilde Krim respectively – came to merge in 1985 into the American Foundation for AIDS Research, one of the world’s leading nonprofit organizations dedicated to the support of AIDS research and HIV prevention.

When the condition that would come to be known as AIDS was first observed among gay men in New York, it caused concern among a group of physicians and scientists that included Mathilde Krim, Ph.D, then a researcher at New York's Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. An informal study group was formed to explore the underlying cause of the diverse symptoms. They demanded a research effort, as well as a public information campaign. In April 1983 Krim founded the AIDS Medical Foundation (AMF) in New York together with a small group of associates to raise private funds to support scientific and medical research on AIDS. In this clip, she talks about the important role of women in the epidemic.

Journalist David Perlman, who was one of the first to write about AIDS, on how celebrities like Rock Hudson, Elizabeth Taylor and Magic Johnson were important in raising awareness.

Actress Sharon Stone, amfAR’s Global Campaign Chair, talks about her AIDS activism and her memories of working with Rock Hudson.

It was said that pressure from Liz Taylor played a part when Ronald Reagan finally mentioned AIDS in his first major speech on the issue in 1987. By then the WHO estimated that 5-10 million people were living with HIV worldwide, and tens of thousands of deaths had been reported. (Reagan's press secretary had been laughing off questions about AIDS at several press conferences since 1982. The shocking documentary short film When AIDS was Funny uses audio from these occasions.)

But back to 1985, a year that saw several important cultural landmarks: the first AIDS-related plays and films. In April, Larry Kramer's The Normal Heart opened Off-Broadway. The play covers the impact the growing epidemic had on him and the New York gay community between 1981-1984, and was almost 30 years later to be made into a film. (Where for instance Julia Robert's character Dr. Emma Brookner was based on the real life hero and early HIV and AIDS researcher Linda Laubenstein.) As Is became the first play about AIDS to make it to Broadway. The Canadian No Sad Songs is said to be the first documentary on the topic. In September, Buddies, the first fictional film to depict the AIDS epidemic, premiered at the Castro Theater in San Francisco, and was shown in a handful of art house movie theaters. It has since then been hard to get hold of, but it was restored and digitalized in 2018 and is now easily available. And, it has aged more than well. The film follows a gay man dying of AIDS-related complications and a volunteer “buddy” that comes to visit him at the hospital. Compared to many of the films that were to follow it is mindblowingly daring.

The "buddy" system in the film Buddies was based on work at the Larry Kramer-founded Gay Men’s Health Crisis. Listen to Kramer talk about the start of GMHC and the buddy system as a sort of self-organized Red Cross activity.

In November, it was time for the first drama on a major network. In An Early Frost Aidan Quinn plays a successful lawyer who learns he is HIV-positive. He returns home, and his family have to deal with the revelation that their son is gay and has a terminal disease. It was criticized for being de-gayed, desexualized, and so clearly aimed at a straight audience that it was more about his family's reactions than about him. But still, the film was a call for compassion and empathy. And, more importantly, it wanted to inform and educate. NBC sent out viewers' guides to hospitals, social agencies and schools, with a fact sheet compiled by the Public Health Service. The film captured one third of that night’s TV audience, and afterwards NBC News had a half-hour report on AIDS. Thousands called a toll-free information line.

A slew of independent films followed, like the seminal Parting Glances and Tongues Untied, but it would take until 1990 to see the first widely released film to deal with HIV and AIDS: Longtime Companion, a funny, gut-wrenching and surprisingly raw and unflinching story of how death decimates a group of friends and lovers. The title was taken from the word used in obituaries at the time for the surviving same-sex partner of someone who had died of AIDS-related complications.

In 1993 it was time for a recap and an educating history lesson in the form of And the Band Played On, based on Randy Shilt’s book with the same name. It chronicled the early years of the epidemic and the work by pioneers like Nobel Prize winner Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and epidemiologist Selma Dritz that led to the discovery and tracking of the virus. Their desperate search for clues and answers, the fight over who in the medical community discovered what, the clash with parts of the gay community over the controversial closing of the bathhouses and the disagreements within the activist movement over what the next steps should be – it was all there. There was also the Patient Zero theory, where one single individual was accused of taking the epidemic to the US. The theory has since been debunked, and was even turned into a musical in Zero Patience. In 2019 there was a documentary about the case; Killing Patient Zero.

Public health physician and epidemiologist Selma Dritz is considered one of the early heroes in the AIDS response for her role in identifying the epidemic during the very first outbreaks. She is credited with being one of the first people to postulate that AIDS was a sexually transmitted infectious disease. Here she talks about those early days – and you can also see an excerpt from the film And the Band Played On, where she was played by actress Lily Tomlin.

At the Pasteur Institute in France, Nobel Prize Winners Françoise Barré-Sinoussi and Luc Montagnier isolated a new retrovirus from a French patient with AIDS symptoms in 1983. They called it lymphadenopathy-associated virus, or LAV. Here she talks about the importance of knowing the history of AIDS

That the central characters in the first films about HIV and AIDS were gay men isn't perhaps a big surprise, but even later on when the demographics of those diagnosed had changed drastically since the early days, the idea of the infected as a gay man prevailed – both in the public awareness and on film. That was about to change.

In 1991, when basketplayer Magic Johnson at the height of his career stated that he was infected, the National AIDS hotline got a massive amount of calls in the days that followed. In a 1994 cover story in Essence Magazine Rae Lewis-Thornton disclosed her HIV-status and became an activist. There was also Elizabeth Glaser who co-founded the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation. Her work raised public awareness about HIV infection in children and she raised funding for the development of pediatric AIDS drugs and research into mother-to-child transmission. These advocates didn't fit the stereotypes. New groups of people were becoming aware of the scope of the crisis.

Even though the face of AIDS had changed, when it was finally time for the first mainstream film about AIDS with major stars, it was again about a gay man. In Philadelphia (1993), Tom Hanks plays a lawyer who gets fired from his firm, with no other apparent reason than that his colleagues have discovered that he is infected with HIV. He turns to an openly homophobic lawyer (Denzel Washington) for help. The film feels dated in many ways now, and just like An Early Frost it was criticized at the time for being "de-gayed" and too aimed at a straight audience. On the other hand, there was none of the usual coming out to the family and/or any drama of that kind around Hank's character's homosexuality. He and his partner (Antonio Banderas) had his family's full support. Either way, the film made a huge impact, being a box office hit and winning two Academy Awards.

There were still very few depictions of women with AIDS, but among the films made in the 1990's you could find examples in Something to Live for: The Alison Gertz Story (about real life AIDS activist Alison Gertz), Kids, Gia and Boys on the Side. The latter centres round three women – a no bullshit black lesbian (Whoopi Goldberg), a prude real estate agent with HIV (Mary-Louise Parker) and a woman (Drew Barrymoore) with a violent boyfriend that the trio leave behind tied to a chair – travelling across America to start new lives, forming a strong bond and being confronted with prejudices of all sorts. How Parker's character got infected isn't something they really go into, but a common trope around women with HIV or AIDS in other films and soaps at the time was to make it very clear that they were innocent victims. Somebody cheated on them, they didn't sleep around, it wasn't their fault. Those mixed messages that young women were getting about sex, sexuality and sexually transmitted diseases were brought up in Amber Hollibaugh's and Gini Reticker's documentary The Heart of the Matter, the first documentary about AIDS among women. It centres round Janice Jirau, an HIV-positive African American who deals with the knowledge that she is ill.

In Pedro Almodóvar's All About My Mother a nun gets pregnant with and infected by a trans woman with HIV, and after their death the baby is miraculously cured from the virus and discussed at an AIDS convention.

Talking about cures: it seemed as if the mainstream film industry felt that they were done on the subject when life saving drugs became available in 1996. The issues of HIV and AIDS almost disappeared from the storylines, until it was time to look back on the earlier years of the epidemic in the miniseries version of Tony Kushner's Angels in America and the film version of the musical Rent. If we were to believe film, the crisis was now over.

While all these things went on, the rightly furious AIDS activist movement peaked in the late 80's and the 90's. In 1987 the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power (ACT UP) was formed, and within the movement there were several media activists who filmed the AIDS crisis from inside and created much needed counterimages of the LGBT community and their battles. There was the video collective DIVA TV (Damned Interfering Video Activist Television), with activists like Gregg Bordowitz, Jean Carlomusto, Catherine Gund and Ellen Spiro, there were people like Maria Maggenti, Sarah Schulman and Jim Hubbard.

They were making their own media, documenting their own history. They motivated others in their fight and documented demonstrations, civil disobedience and media reactions to the group. In their first action, the women of ACT UP decided to go after Cosmopolitan when the magazine published an article with the headline "Reassuring News About AIDS: A Doctor Tells Why You May Not Be At Risk". 150 activists protested outside the Hearst building chanting and holding signs with slogans like "Yes, the Cosmo girl CAN get AIDS!". It brought national attention to the issue and the filmed material of the event was edited into a short by Carlomusto and Maggenti: Doctors, Liars, and Women: AIDS Activists Say No To Cosmo.

The hundreds of hours these activists filmed and preserved, and the archives that they have developed – for instance the ACT UP Oral History Project – are invaluable, and are what have made many of the recent revisits to the early years of the AIDS crisis possible. Documentaries like Sex in an Epidemic, United In Anger: A History of ACT UP and the Oscar-nominated documentary How To Survive a Plague helped break the silence on AIDS again. Together with recent fictional recreations of the early days of AIDS activism, like the French 120 BPM and the Swedish series Don't Ever Wipe Tears Without Gloves, they have raised awareness, conveyed to new generations what it was like back then – and made it loud and clear that this crisis is far from over. People are still getting infected, there is still stigma. There are more stories to be told.

When most people in the western world got access to proper health care and life saving drugs, others didn't, and too many still don't. HIV remains one of the most serious global health threats, and disproportionately affects minority communities, poorer urban areas, transgender people, women in sub-Saharan Africa. The film faces of AIDS have changed accordingly. The life and struggle of new generations of activists, politicians, doctors and people living with HIV, both in the US and other parts of the world, is documented in films like Fire in the Blood and The Lazarus Effect – films about the fight to get access to the drugs for all, and what incredible effects the drugs quickly can have on those who do.

The epidemic is featured in fictional films like Yesterday and Precious, and just like An Early Frost did in 1985, films like Life Support want to educate through entertainment. These films all show how the virus has hit women.

What if more stories like that had been told in the early 80's? Would it have changed anything? Maybe. Probably. Now, what if more movies had featured condoms as a natural part of sex, and not just as a fun gimmick in high school films? Would it have changed anything? It blows your mind to think about it, and it makes you realise, again, how affected we are by what we see or do not get to see – and the devastating effects the lack of certain stories, certain groups and certain elements in the movies can have on real life.

Published: 2020-01-17