The history of HIV and AIDS is not only about medical concerns, but of social exclusions and political struggles as well. From the outbreak of the epidemic, inequality and patterns of discrimination affected both the spread of the disease and various responses to it. As the epidemic almost immediately became associated with some of the most marginalized groups in the society, homophobia, racism, and disdain for people who use drugs provoked many of the early responses. But perhaps lesser known, gender subordination and sexism also played an essential role in fueling the epidemic.

Today, 19.6 million women are living with HIV worldwide, comprising 52% of the total number of people living with HIV. Every week, predominantly in sub-Saharan Africa, 6000 young women become infected. As Salvadorian-Canadian activist and public health official Zonibel Woods stated in her speech at the 2008 International AIDS conference in Mexico City: “These numbers serve as a stark reminder of a reality that is too often ignored: without adequate resources for programs that target women, success in the fight against HIV will never be achieved.”

Salvadorian-Canadian activist and public health official Zonibel Woods speaks at the 2008 International AIDS conference in Mexico City.

Indeed, Woods is right on two accounts. First, the particular ways in which HIV and AIDS affect women has continuously and disastrously been ignored. Second, and still, the global response to AIDS must necessarily address women and gender subordination in order to succeed.

A third remark might be added to the list, however. To simply target women (assumingly “from above”) is not enough, as long as women are not seen as important actors in themselves. “Women have been counted and targeted for intervention,” as anthropologist Ida Susser notes, “[but] the recognition of women as significant actors and agents of transformation has yet to be fully documented.”

To be sure, rather than agents of transformation, people living with HIV and women with HIV in particular are often depicted as passive victims of the epidemic. Therefore, in contrast to such portrayals, Susser’s point is worth repeating. Of course, women with HIV have suffered immensely from the disease, but they have also resisted. Across the globe, women, including women with HIV themselves, have struggled collectively towards ending the devastating effects of the HIV and AIDS epidemic.

The invisible epidemic

In The Invisible Epidemic (1992), American journalist Gena Corea chronicled the ways in which women remained absent in early responses to the AIDS epidemic. Although, as she documents, the first woman with AIDS had been reported in late 1981, just months after the very first reported cases of AIDS involving five gay men in Los Angeles, most women with AIDS-related illnesses were not reported at all. Their symptoms simply did not fit the first restrictive definitions of AIDS.

Of course, definitions are often restrictive in early stages of any new disease, when epidemiologists work to differentiate the new phenomenon from other previously known diseases. Even so, the unwillingness to recognize women with AIDS were not random. It drew upon a long history of medical hostility towards women. Indeed, when the modern medical science was gradually established throughout the nineteenth and twentieth century, women were not only kept out of the medical profession, but male doctors and scientists also misrepresented or ignored medical issues facing women, especially Black women and women of color.

With AIDS, this history repeated itself. As Corea writes: “When it was crucial for the medical community to recognize, treat, and halt a fatal sexually transmitted disease that appeared first in a series of ‘others’—gay men, African-American and Latino drug addicts, women of color—there was a problem: the medical system itself was filled with contempt for ‘the other’.”

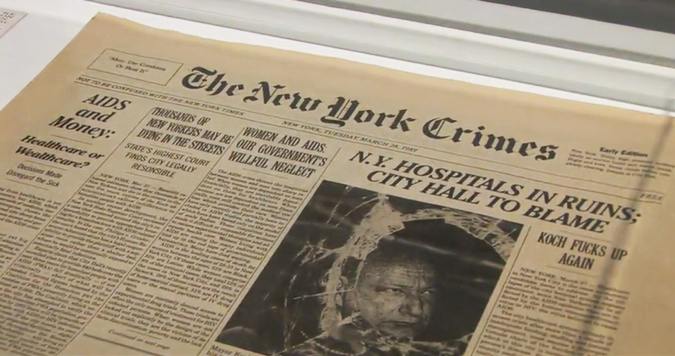

True. From the outset of the epidemic, panic against “the other” were set loose. In media and medicine alike, AIDS was linked to deviancy. Notions of “gay cancer” and “the gay plague” permeated the tabloid press. If not understood to affect gay men exclusively, AIDS were seen as a disease of “risk groups” or of the so-called 4-H Club: homosexuals, heroin users, hemophiliacs, and Haitans. Within this emerging framework, women in general had no place, unless as the oft-forgotten but important nurses and care workers.

Only as sex workers did women sometimes capture serious attention from AIDS research and media. But like other “risk groups,” women involved in the sex trade were not considered primarily in terms of their own well-being, but instead as potential threats to the perceived “general population.” Just consider the following clip from the 1986 film AIDS – Metaphor and Reality, in which immunologist Nathan Clumeck draws a sharp distinction between gay men, drug users, and sex workers on the one hand, and the general population on the other.

Professor of immunology at the University of Brussels Nathan Clumeck interviewed for the 1986 Face of AIDS documentary AIDS – Metaphor and Reality.

Even later, when focus shifted from risk groups to risk behaviors, women’s particular risks were rarely acknowledged, even as condomless heterosexual intercourse became a primary mode of HIV transmission. In 1990, for instance, The Myth of Heterosexual AIDS by journalist Michael Fumento reached bestseller status, with arguments presumably proving the unlikeliness of women being transmitted with HIV at all.

Fighting back: ACT UP’s Women Caucus

Yet, the invisibility of women with AIDS did not stand uncontested. From the mid-1980’s, grassroots activists, independent journalists, and critical researchers began calling attention to the political and social context of the AIDS epidemic, including women’s specific vulnerability to the disease.

In the United States, the most sustained campaign aimed at recognizing the situation of women living with HIV and AIDS was spurred following an article published by Cosmopolitan magazine in early 1988. In the article, psychiatrist Robert E. Gould claimed that women had no reason to worry about acquiring HIV.

In response to the article, ACT UP (the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power)—founded by lesbians and gay men less than a year earlier—organized direct-action protests targeting the offices of Cosmopolitan. They also confronted Gould himself, as evidenced in Jean Carlomusto’s documentary Doctors, Liars and Women. Even more so, the “Say No to Cosmo!” campaign brought about the formation of ACT UP’s Women’s Caucus, which would continue to highlight the political context of women living with HIV and AIDS, across race, class, and sexual orientation.

In particular, the Women’s Caucus organized intensely to change the official CDC definition of AIDS, which did not cover symptoms most common among women, including low T-cell counts and cervical cancer. By way of this exclusion, many women with AIDS (alongside people who use drugs) did not benefit from the first gains won by AIDS activism in the 1980’s, such as the right to AIDS healthcare, protection from discrimination, and participation in early antiviral trials.

While protesting the CDC, the Women’s Caucus mobilized thousands of activists, many of whom were themselves HIV positive (with or without the official diagnosis), such as Iriz de la Cruz, Keri Duran, Phyllis Sharp, and Marina Alvarez. In early 1993, following four years of ACT UP campaigning, CDC finally changed their official definition of AIDS, thereby increasing the official national number of women with AIDS with almost 50 percent.

In the Face of AIDS Film Archive, some traces of ACT UP are present as well, including footage from one of their 1988 demonstrations in New York’s Central Park. At this particular event, AIDS activist and needle exchange organizer Yolanda Serrano spoke about the interconnected needs of people who use drugs and the minority communities of the city.

“We have to do a public outcry”: Yolanda Serrano speaks at a 1988 ACT UP demonstration in Central Park, New York.

Community responses from the global South

Although highly significant in its own right, the history of ACT UP’s Women’s Caucus is linked to other efforts globally that advocated for the recognition of women with AIDS. As historian Jennifer Brier notes, “some of the strongest and clearest feminist responses to AIDS in the late 1980s came from the global South.” Organizations such as ABIA in Brazil, EMPOWER in Thailand, and the Centre de Promotion des Femmes Ouvrières in Haiti pushed international health and aid institutions to provide resources, funding, and support for work related to women and AIDS.

In the same spirit, the International Community of Women Living with HIV and AIDS (ICW) was established at the 1992 International AIDS Conference in Amsterdam. To date, it is the only international network run by and for women with HIV, working with information, services, and support for HIV positive women. Among their members, Indonesian activist Frika Chia Iskander was featured in the 2008 Face of AIDS documentary Women at the Frontline.

South Africa, finally, was another key site for feminist responses to AIDS. Here, around the end of the apartheid regime in 1994, the women’s movement in general was strong, and health was one of their top priorities, as seen for instance in media projects such as Agenda journal and Speak magazine. Partly drawing upon this work of women’s health activism, South African epidemiologist Zena Stein introduced in 1990 the concept of microbicides, a prevention method that women themselves can use.

However, the HIV virus continued to spread in South Africa throughout the 1990’s, predominantly in poor black townships and communities. As Archbishop Desmond Tutu was credited saying, “AIDS is our new apartheid.” In 1998, responding to the national neglect of HIV and AIDS, the Treatment Action Campaign was founded. Linda Mafu, one of their eventual spokespersons, was interviewed in for the Face of AIDS Film Archive in 2006.

Linda Mafu, in a 2006 interview on the founding of Treatment Action Campaign (TAC), and women’s rights in South Africa.

Feminist doctors

Following activist pressure from below, the issues facing women with AIDS eventually received attention from medical professionals as well. Here, the history of American physician Jonathan Mann serves as an excellent case in point.

A key figure in the global response to HIV and AIDS, Jonathan Mann initially focused his work within AIDS research on individual behaviors, rather than structural power dynamics. In the late 1980’s, however, after leaving his work at the World Health Organization, Mann developed an approach to the AIDS epidemic centered around notions of human rights and public health more broadly. As the founder and director of HealthRight International, he was interviewed for the Face of AIDS Film Archive in 1994, outlining his ideas and repeating the importance of challenging the social and economic conditions—including gender subordination—that continues to underpin the HIV and AIDS epidemic.

As he states in the interview: “You can’t make up for societal discrimination, marginalization, or stigmatization through simply providing public health measures, like having some clinics, brochures, condoms, information, education – services of that kind. You have to address the underlying problem itself.”

Jonathan Mann in a 1994 Face of AIDS interview, discussing the social conditions that encourages the spread of HIV.

Women in the history of HIV and AIDS

At first glance, the inclusion of women as part of the history of HIV and AIDS might seem self-evident. Yet, it is worth recognizing that “women and AIDS” became an issue not only because of plain medical facts, but because women and women with HIV in particular struggled to become part of the HIV and AIDS conversation.

Throughout the four last decades and in coalition with other activists, women with HIV have worked to address—among many other things—the exclusion of women from medical research, misrepresentations of AIDS in the media, the lack of access to treatment and prevention, and the right to healthcare more broadly. This struggle continues.

More reading

- ACT UP, Women, AIDS, and Activism, Boston: South End Press, 1990.

- Brier, Jennifer, Infectious Ideas: U.S. Political Responses to the AIDS Crisis, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

- Corea, Gena, The Invisible Epidemic: The Story of Woman and AIDS, New York: Harper Collins, 1992.

- Patton, Cindy, Globalizing AIDS, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

- Susser, Ida, AIDS, Sex, and Culture: Global Politics and Survival in Southern Africa, Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

- Treichler, Paula, How to Have Theory in an Epidemic: Cultural Chronicles of AIDS, Durham: Duke University Press, 1999.

Published: 2020-01-17